Table of Contents

Nursing is more than a profession; it is a calling grounded in compassion, skill, and a profound commitment to human well-being. At the very heart of this demanding and rewarding field lies nursing ethics, the moral compass that guides nurses through complex situations, shapes their interactions with patients and colleagues, and defines the very integrity of their practice. In an era of rapidly advancing medical technology, shifting societal values, and increasing healthcare complexities, a robust understanding of nursing ethics is not merely beneficial – it is absolutely essential.

This guide aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of nursing ethics, covering its foundational principles, common dilemmas, decision-making frameworks, professional codes, and its evolving role in contemporary healthcare.

What is Nursing Ethics?

Nursing ethics is a specialized branch of applied ethics that focuses on the moral issues arising in the context of nursing practice, theory, education, and research. It involves the critical examination of values, beliefs, and actions related to the care of patients, families, communities, and populations. Unlike broader medical ethics, which might focus more heavily on physician responsibilities or biomedical research, nursing ethics places a distinct emphasis on the unique relationships nurses build, the specific duties they undertake, and the particular vulnerabilities they encounter in their daily work.

It encompasses:

- Moral Principles: Understanding and applying fundamental ethical tenets like autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice in nursing scenarios.

- Professional Values: Upholding standards of care, integrity, compassion, advocacy, and respect for human dignity.

- Character and Virtue: Cultivating personal moral qualities essential for ethical practice, such as courage, honesty, empathy, and trustworthiness.

- Ethical Decision-Making: Developing the skills to identify, analyze, and resolve ethical dilemmas encountered in practice.

- Social Responsibility: Recognizing the nurse’s role in addressing broader health inequities and advocating for just healthcare policies.

Essentially, nursing ethics provides the framework for nurses to navigate the “shoulds” and “oughts” of their profession – determining the right course of action when faced with conflicting values, duties, or potential outcomes. It is the bedrock upon which trusting nurse-patient relationships are built and maintained.

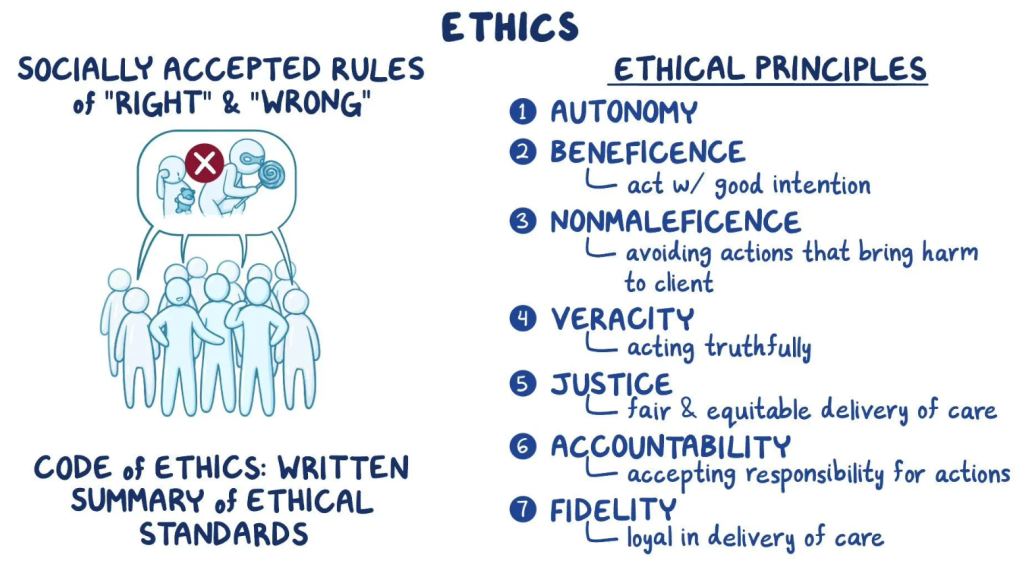

The Cornerstone Principles of Nursing Ethics

While ethical situations can be infinitely varied, a set of core principles provides a consistent foundation for analysis and decision-making in nursing ethics. These principles, often derived from bioethics, are universally recognized guides for ethical conduct:

- Autonomy (Self-Determination):

- Definition: Respecting the right of competent individuals to make informed decisions about their own healthcare, free from coercion or undue influence.

- In Practice: This involves obtaining informed consent before procedures, respecting treatment refusals (even if the nurse disagrees), providing patients with all necessary information to make choices, and supporting their decisions. It requires assessing a patient’s capacity to make decisions and involving appropriate surrogates when capacity is lacking. Upholding autonomy is a central challenge and goal within nursing ethics.

- Example: Ensuring a patient fully understands the risks and benefits of a proposed surgery before signing the consent form, and respecting their decision if they decline.

- Beneficence (Doing Good):

- Definition: The obligation to act in ways that promote the well-being and best interests of the patient.

- In Practice: This includes providing competent and compassionate care, preventing harm, actively helping patients achieve positive health outcomes, and balancing potential benefits against risks. It involves advocating for patient needs and acting kindly. Beneficence is a driving force behind compassionate nursing ethics.

- Example: Administering pain medication promptly, repositioning a patient to prevent pressure ulcers, or providing emotional support to a distressed family member.

- Non-maleficence (Do No Harm):

- Definition: The fundamental duty to avoid causing harm or injury to patients, either intentionally or unintentionally.

- In Practice: This principle requires nurses to practice safely, maintain clinical competence, be vigilant about potential risks (like medication errors or infections), report errors honestly, and avoid actions that could inflict physical or psychological harm. It is arguably the most basic tenet of healthcare and nursing ethics.

- Example: Carefully checking medication dosages and patient identifiers before administration, using proper sterile technique during procedures, or raising concerns about unsafe staffing levels.

- Justice (Fairness):

- Definition: Treating patients fairly and equitably, ensuring a just distribution of resources, risks, and benefits.

- In Practice: This involves providing the same high standard of care to all patients regardless of their race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender identity, sexual orientation, or other personal characteristics. It also extends to broader issues like fair allocation of scarce resources (beds, ventilators, staff time) and advocating for policies that address health disparities. The principle of justice is critical in contemporary discussions of nursing ethics and health equity.

- Example: Ensuring all patients on a unit receive timely attention based on need, not personal preference, or advocating for translation services for non-English speaking patients.

- Fidelity (Loyalty and Promise-Keeping):

- Definition: Being faithful to one’s commitments, responsibilities, and promises. This includes loyalty to patients, colleagues, the profession, and oneself.

- In Practice: This means keeping promises made to patients (e.g., “I’ll be back in 10 minutes”), maintaining confidentiality (unless there’s a clear mandate to disclose), advocating for patient wishes, and being a reliable member of the healthcare team. Fidelity builds trust, a cornerstone of the nurse-patient relationship and sound nursing ethics.

- Example: Protecting a patient’s private health information, following through on commitments made during patient handovers, or supporting a colleague who is upholding ethical standards.

- Veracity (Truthfulness):

- Definition: The obligation to be truthful and honest with patients and others.

- In Practice: This involves providing accurate information about diagnoses, treatments, and prognosis in a way the patient can understand. It also includes being honest about errors or near misses. While sometimes challenging (e.g., delivering bad news), veracity is fundamental to building trust and respecting patient autonomy. Honest communication is vital in nursing ethics.

- Example: Clearly explaining the potential side effects of a new medication, honestly answering a patient’s questions about their condition, or disclosing a medication error according to institutional policy.

These principles often interact and sometimes conflict, leading to ethical dilemmas that require careful consideration and application of sound nursing ethics.

Navigating Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing Practice

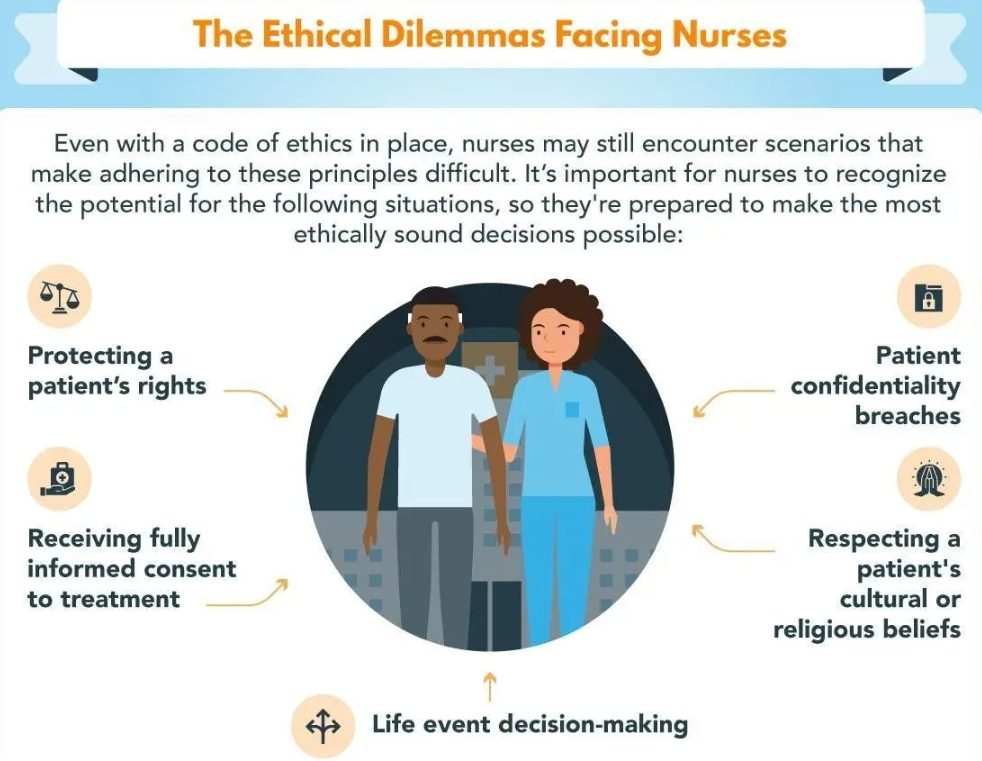

Ethical dilemmas in nursing arise when there is a conflict between two or more ethical principles, values, or obligations, and choosing one course of action means compromising another. Nurses frequently encounter such situations due to the intimate nature of their work and the high stakes involved in healthcare. Understanding nursing ethics helps navigate these challenging scenarios.

Common ethical dilemmas in nursing include:

- End-of-Life Care: Conflicts often arise regarding initiating or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, respecting advance directives (like DNR orders), managing pain versus hastening death (doctrine of double effect), and supporting patient/family wishes that may conflict with medical recommendations. Applying nursing ethics principles like autonomy and non-maleficence is crucial here.

- Resource Allocation: Nurses often face dilemmas related to distributing scarce resources, such as ICU beds, ventilators, or even their own time during periods of understaffing. Justice and beneficence frequently clash in these situations.

- Informed Consent: Challenges arise when a patient’s capacity to consent is questionable (e.g., due to dementia, mental illness, or sedation), when dealing with minors who can assent but not consent, or when families pressure patients into decisions. Respecting autonomy while ensuring patient safety requires careful ethical deliberation.

- Confidentiality vs. Duty to Warn/Protect: Nurses have a duty to protect patient confidentiality (fidelity), but this can conflict with the duty to protect others from harm (e.g., reporting contagious diseases, suspected abuse, or threats of violence). Balancing these duties is a complex aspect of nursing ethics.

- Cultural and Religious Conflicts: Patient or family beliefs may conflict with recommended medical treatments (e.g., blood transfusions, certain dietary restrictions). Nurses must respect cultural diversity (autonomy, justice) while upholding standards of care and promoting well-being (beneficence).

- Truth-Telling vs. Protecting from Distress: Deciding how much information to share, especially when the news is bad or could cause significant emotional distress, can be difficult. Balancing veracity with non-maleficence requires sensitivity and ethical judgment.

- Dealing with Incompetent or Unethical Colleagues: Nurses may witness colleagues providing substandard care, violating policies, or behaving unethically. They face a dilemma between loyalty to colleagues (fidelity) and their primary duty to protect patients (non-maleficence, beneficence). Reporting concerns is often an ethical obligation dictated by professional codes and nursing ethics.

- Patient Advocacy vs. Institutional Constraints: Nurses may advocate for patient needs that conflict with hospital policies, resource limitations, or physician orders. Balancing patient advocacy (beneficence, fidelity) with professional responsibilities and institutional realities requires courage and ethical reasoning.

Facing these dilemmas can lead to moral distress – the psychological unease experienced when one knows the ethically correct action to take but feels constrained from doing so. A strong foundation in nursing ethics can help nurses identify, analyze, and cope with these situations more effectively.

Ethical Decision-Making Models in Nursing

When confronted with an ethical dilemma, having a systematic approach can help ensure all relevant factors are considered and a justifiable decision is reached. While no single model is perfect, structured frameworks promote clarity and consistency in applying nursing ethics. Many models share common steps:

- Identify and Clarify the Ethical Problem: What exactly is the issue? What values or principles are in conflict? Is it truly an ethical dilemma, or a communication breakdown or legal issue?

- Gather Information: Collect all relevant facts about the patient’s medical condition, prognosis, values, preferences, capacity, family situation, and the perspectives of all involved stakeholders (patient, family, healthcare team).

- Identify Stakeholders: Who is affected by this situation and the potential decisions? (Patient, family, nurses, physicians, other staff, institution, community).

- Identify Options/Alternatives: Brainstorm possible courses of action. What are the potential benefits and harms of each option?

- Apply Ethical Principles and Theories: Analyze the options through the lens of core nursing ethics principles (autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, fidelity, veracity). Consider relevant ethical theories (e.g., utilitarianism – greatest good for greatest number; deontology – duty-based ethics).

- Consult Professional Codes and Guidelines: Refer to documents like the ANA Code of Ethics or ICN Code of Ethics for guidance relevant to the situation. Consult institutional policies.

- Consider Personal Values (Self-Reflection): Acknowledge your own beliefs and biases, ensuring they don’t unduly influence the decision in a way that overrides patient autonomy or professional obligations. Understanding ethics in nursing involves this level of self-awareness.

- Collaborate and Consult: Discuss the dilemma with colleagues, mentors, supervisors, or an institutional ethics committee. Interdisciplinary input often provides valuable perspectives.

- Make a Decision and Act: Choose the course of action deemed most ethically justifiable based on the analysis. Implement the decision thoughtfully and compassionately.

- Evaluate the Outcome: Reflect on the decision-making process and the consequences of the action taken. What was learned? How could similar situations be handled in the future? This evaluation strengthens future application of nursing ethics.

Using such models helps ensure decisions are reasoned, transparent, and defensible, rather than purely intuitive or reactive.

Professional Codes of Ethics: Guiding the Nurse

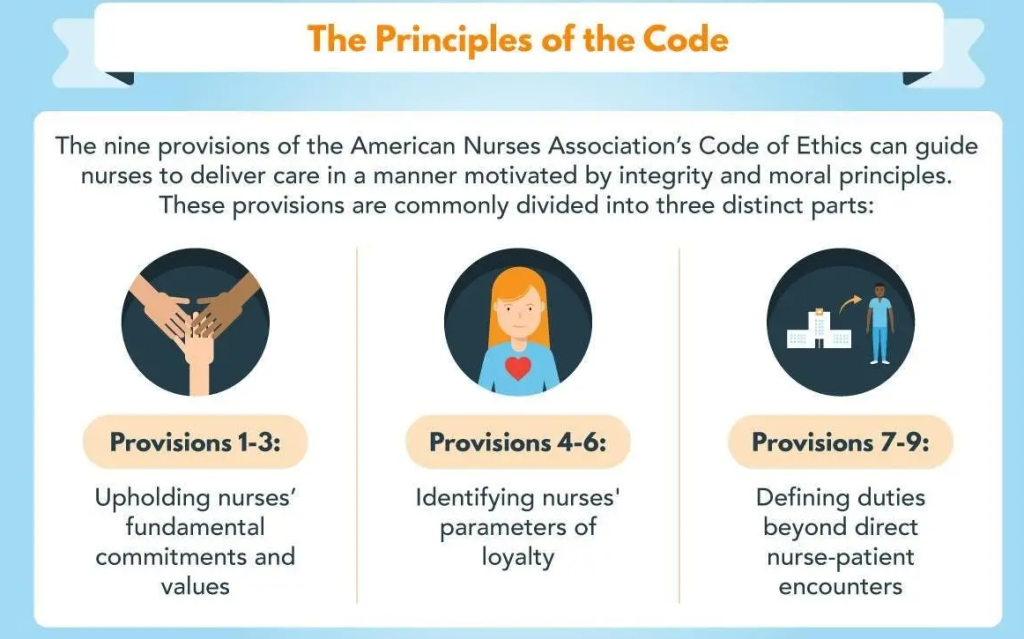

Professional codes of ethics serve as foundational documents for nursing ethics. They articulate the primary goals, values, and obligations of the nursing profession, providing standards for practice and guidance for navigating ethical challenges. Two key codes are:

- The American Nurses Association (ANA) Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements:

- This code outlines nine provisions covering fundamental values and commitments, the nurse’s primary commitment to the patient, advocacy for patient rights, responsibility and accountability, duties to self (promoting health and safety, maintaining competence, preserving integrity), establishing and maintaining an ethical work environment, advancing the profession, collaborating to meet health needs, and upholding nursing values and social justice.

- The interpretive statements provide detailed guidance for applying each provision in practice. It is a cornerstone document for nursing ethics in the United States.

- The International Council of Nurses (ICN) Code of Ethics for Nurses:

- This code provides ethical guidance for nurses worldwide. It outlines four principal elements that frame standards of ethical conduct: nurses and people (primary responsibility is to those needing care), nurses and practice (maintaining competence, personal health), nurses and the profession (role in developing professional knowledge, standards), and nurses and co-workers (collaboration, safeguarding patients when care is endangered).

- It emphasizes respect for human rights, cultural rights, dignity, and treating people with respect.

These codes are not legal documents in themselves (though violations can have legal implications via licensing boards), but they represent the profession’s collective understanding of its ethical responsibilities. They serve as:

- A statement of the ethical values and commitments of nursing.

- A guide for ethical decision-making and conduct.

- A standard for professional accountability.

Familiarity with and adherence to these codes are essential components of ethical nursing practice and reinforce the importance of nurse ethics.

The Intersection of Law and Nursing Ethics

While closely related, law and ethics are distinct. Law represents the minimum standard of conduct deemed acceptable by society, often enforced through regulations and penalties. Nursing ethics, on the other hand, often represents a higher standard, reflecting moral obligations, values, and aspirations of the profession.

- Overlap: Many legal requirements align with ethical principles (e.g., laws against negligence align with non-maleficence; informed consent laws align with autonomy).

- Difference: An action might be legal but ethically questionable (e.g., providing minimal, legally compliant care that falls short of compassionate best practice). Conversely, an ethically driven action might, in rare cases, conflict with a specific law or policy, creating profound dilemmas.

- Guidance: Laws (like Nurse Practice Acts, HIPAA, Patient Self-Determination Act) provide external rules, while nursing ethics provides an internal compass based on principles and values.

Nurses must be knowledgeable about both legal requirements and ethical obligations to practice safely and responsibly. Understanding the interplay between law and nursing ethics is crucial for navigating complex situations where legal and moral duties may seem to conflict.

Nursing Ethics in Specialized Areas

While the core principles remain constant, their application can have unique nuances in different nursing specialties:

- End-of-Life Care: Emphasis on autonomy (advance directives), non-maleficence (pain management vs. hastening death), beneficence (comfort care), and supporting families through grief.

- Pediatrics: Balancing parental rights with the child’s best interests and evolving capacity for assent/consent (justice, beneficence, autonomy).

- Mental Health Nursing: Complexities around capacity, involuntary treatment, confidentiality vs. duty to protect, stigma reduction (autonomy, non-maleficence, justice).

- Critical Care: Frequent dilemmas involving resource allocation, end-of-life decisions for incapacitated patients, balancing aggressive treatment with quality of life (justice, autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence).

- Public Health Nursing: Focus on community well-being, social justice, addressing health disparities, balancing individual liberty with public safety (e.g., mandatory vaccinations, quarantine) (justice, beneficence).

- Nursing Research: Protecting vulnerable subjects, ensuring informed consent, maintaining confidentiality, ensuring scientific integrity (autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice).

- Nursing Informatics: Issues related to data privacy and security (HIPAA), ethical use of technology (AI, telehealth), ensuring equitable access to digital health tools (fidelity, non-maleficence, justice).

In every specialty, a strong grasp of fundamental nursing ethics principles allows nurses to tailor their ethical reasoning to the specific context.

Cultivating Ethical Competence and Resilience

Ethical competence is not innate; it is developed and honed throughout a nurse’s career. Cultivating this competence requires ongoing effort and commitment:

- Education: Foundational nursing ethics education in nursing programs and ongoing continuing education are essential.

- Mentorship: Learning from experienced nurses who model ethical practice and can provide guidance.

- Reflective Practice: Regularly thinking critically about one’s own actions, motivations, and ethical challenges encountered. Journaling can be a useful tool.

- Case Study Discussions: Analyzing real or hypothetical ethical dilemmas with peers helps develop analytical skills and explore different perspectives.

- Ethics Committees and Rounds: Participating in or consulting with institutional ethics committees provides expertise and support for complex cases.

- Ethical Leadership: Nurse leaders play a crucial role in fostering an ethical climate where staff feel safe to raise concerns and discuss dilemmas openly.

- Self-Care: Addressing moral distress and preventing burnout through self-care strategies is vital for maintaining ethical sensitivity and resilience.

Developing ethical competence is a continuous journey, integral to professional growth and the consistent application of sound nursing ethics. Need help with completing academic assignments about nursing ethics? Engage Nursing Papers for professional help with nursing research papers, term papers, TEAS exams and other assignments. Besides, we also have experienced writers to help you with crafting impactful essays, case studies, thesis and dissertations.

Emerging Challenges and the Future of Nursing Ethics

The landscape of healthcare is constantly changing, bringing new ethical challenges to the forefront. The future of nursing ethics will need to address:

- Technological Advances: Artificial intelligence (AI) in diagnostics and decision support, robotics, genetic engineering, and big data analytics raise questions about privacy, bias, accountability, and the human element of care.

- Genomic Medicine: Issues related to genetic testing, screening, privacy of genetic information, and potential for discrimination.

- Global Health Disparities: Nurses’ roles and responsibilities in addressing health inequities locally and globally, including access to care, resource distribution, and pandemic response.

- Aging Population and Chronic Disease: Increasing demands on the healthcare system, complex care needs, and ethical issues related to long-term care, dementia, and palliative care.

- Social Determinants of Health: Growing recognition of how factors like poverty, education, housing, and racism impact health, raising ethical obligations for nurses to advocate for social justice.

- Workforce Challenges: Issues like staffing shortages, workplace violence, and burnout impact the ethical climate and nurses’ ability to provide optimal care.

Nursing ethics must evolve to meet these challenges, requiring ongoing dialogue, research, and adaptation of ethical frameworks and professional codes. The core principles will likely remain relevant, but their interpretation and application will need to address these new realities.

Conclusion: The Enduring Importance of Nursing Ethics

Nursing ethics is far more than an academic subject or a set of abstract rules; it is the living, breathing moral core of the nursing profession. It guides everyday actions, informs responses to crises, underpins patient trust, and shapes the nurse’s professional identity. From the bedside to the community, from education to policy advocacy, nursing ethics provides the essential framework for navigating the complex moral landscape of healthcare.

Adhering to ethical principles, engaging in thoughtful decision-making, utilizing professional codes, and continuously developing ethical competence are not optional extras—they are fundamental obligations. By embracing the principles and practices of nursing ethics, nurses honor their commitment to patients, uphold the integrity of their profession, and contribute to a more just and compassionate healthcare system. The profound responsibility and privilege of nursing demand nothing less than an unwavering commitment to the highest standards of nursing ethics.